Shortly before I retired fully from my three decades as an academic at The University of Kent I wrote a short series of blog posts on aspects of my career (starting here). They were drafted in a bit of a hurry in response to a request from one of my colleagues – who was, it transpired, already contemplating a ‘retirement conference’ in my honour and wanted a little biographical material; they were far from exhaustive. Within that handful of posts there is mention of the person who kick-started my career in science in the mid-1970s and who influenced it from time to time for the next thirty five years or so …

When I first came across John Enderby he was ‘Professor Enderby’ and the head of the Department of Physics at the University of Leicester, where I was an undergraduate student. It was years later that he became a Fellow of the Royal Society and was subsequently knighted. Sadly, John died at the beginning of August in 2021; he was 90 years old. Only now, a year later and after the worst of the COVID-related restrictions and fears are in the past, was it practicable to hold a meeting to celebrate his considerable contributions to science. As one of the few people still around who had worked with him during his time at Leicester (and for whom the organisers had contact details) I was asked to contribute to the short talks planned for the first day of the celebratory meeting. It was an honour to accept the invitation. This blog post is, in essence, the distillate of my talk on September 5th at ‘Understanding the Structure of Liquids: Celebrating John Enderby’s Scientific Legacy’ at The University of Bristol.

|

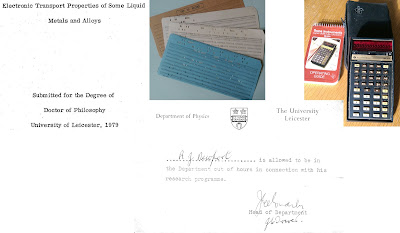

| Central to the images above is a monochrome image of the ESR spectrometer we used for our allocated final year research project. It was taken by the departmental technician who acted as official photographer. I was given a copy, as was my project partner, which I annotated by hand and included in my project report – the front cover of which is reproduced on the left. The report itself was typed using a fairly basic typewriter; the equations were inserted by hand as were all graphs, diagrams and tables. I generated a carbon copy for myself; there were no photocopiers in the department. Very few people possessed an electronic calculator at the time, which were still fairly primitive back then – and prohibitively expensive, so calculations were undertaken using logarithms and slide rules. |

Unbelievably to us at the time, my project partner and I were invited to a party at John Enderby’s house to celebrate his research group’s success in winning their first truly substantial research grant from what was then the UK Science Research Council. Being made to feel welcome – a part of the team despite our particularly junior status – had a great impact; it afforded one of the many lessons I have sought never to forget. However, there were things to learn from the day-to-day as well. For instance, John’s habit of wandering through the labs. most days, coffee cup in hand, is one deceptively simple example. He’d engage anyone and everyone in conversation about what they were doing; keeping himself abreast of developments of course but, in the process, bolstering the confidence of undergraduate and early-career researchers alike … whilst also keeping them on their toes. With my time as an undergraduate student coming to a close I began the process of sorting out what my next step might be. I had obtained a place on a PGCE course, so secondary school teaching was one attractive option. However, despite enduring feelings of inadequacy, my ambitions were focused on the desire to dive into research. Thus, despite fascinating offers in the areas of ionospheric physics and geophysics, it took me relatively little time to accept John’s offer to join his group as a PhD student.

As it turned out, after a period of study leave in the USA, John left Leicester for a post in Bristol only a year after my PhD began so I never did benefit from his continued day-to-day supervision. One of his Leicester colleagues, Alan Howe, bravely took me on and became my key early-career mentor in John’s stead. John and I stayed in touch however and met on innumerable occasions through the years. This included the period of his tenure as Physical Secretary and Vice-President for The Royal Society, during which time I recall being treated to an excellent meal at the Army & Navy Club so that he could debrief me on my department’s performance in the recent Research Assessment Exercise. I’ve lost count of the number of supportive references etc. he wrote for me, and I have cause to be particularly grateful for his gentle nudges into what became an extensive involvement with the UK Research Councils (see here).

During the first couple of years after the move to Bristol in 1976 John would visit his old department at Leicester often. On just such a visit he wandered into my small lab. for a chat. I wasn’t there, so he had to make do with my latest written log entries. At this point I ought to point out that John was incredibly enthusiastic when ostensibly exciting results emerged, but occasionally this enthusiasm misfired. In the longer term it was never a problem: as the saying goes, first attributed to Nobel Laureate Linus Pauling, “The best way to have a good idea is to have lots of ideas and throw away the bad ones.” John was a master of this approach, which I heartily applaud, but in the short term there are risks. He thought that my data on the resistivity of liquid palladium-silver alloys might represent the first evidence for ‘paramagnons’ in a liquid metal and he duly shared this idea widely. It didn’t, as I demonstrated through further measurement in the months that followed. No long-term harm was done; John was an excellent scientist: when I had generated more reliable data we simply moved on – that’s how science works.

I hope I possess sufficient wisdom to choose to learn from others: to learn what works and what ought to be avoided. I learnt a great deal from John. Indeed, from my days as an undergraduate student, through various transitory research posts and to my thirty years as an academic with my own thoroughly interdisciplinary research team, John remained a person to learn from. I am thankful for the privilege of having known him.

* I had applied for a Joint Honours degree in Physics & Chemistry, but due to an ‘administrative oversight’ I arrived at Leicester to find myself registered for their BSc Physics programme. Lacking the self-confidence to anything other, I simply ‘went with the flow’. I have used the term serendipity often in relation to my career: this apparently random event is perhaps an early example.

No comments:

Post a Comment